Does the Cochrane Review put the mask debate to bed? Or is it bad science?

Response to Cochrane Report 2022 Update on Physical interventions to interrupt or reduce the spread of respiratory viruses.

An updated Cochrane Review has suggested that ‘masks don’t reduce the spread of COVID in the community’. Does this finally put to bed the ongoing debate which continues to pit those who think masks are an aberration against the growing body of evidence showing benefit? Unfortunately not because, in simple terms, it isn’t good science. This latest Review, which perpetuates the errors made in its prior iterations, has delivered a further undermining of the interventions that could, in the event of a future similar pandemic, save lives.

We are not alone in this thinking: since the Cochrane Review was published a number of experts have openly questioned the validity of the conclusions.

Jason Abaluk, an Economist at Yale University and one of the authors of the largest and most comprehensive study on mask effectiveness that demonstrated that mask wearing does reduce covid transmission said: ‘To say “We asked some people to wear masks and they didn’t get healthier, therefore, there is no evidence that masks are effective” is crazy given well-powered studies at the community level, RCTs [Randomised Controlled Trials] in hospitals, and laboratory studies measuring viral load that all show effects.’ Put another way, the best studies tell us that masks do something real to reduce disease transmission, but this meta-analysis degrades that by diluting them with poor data.

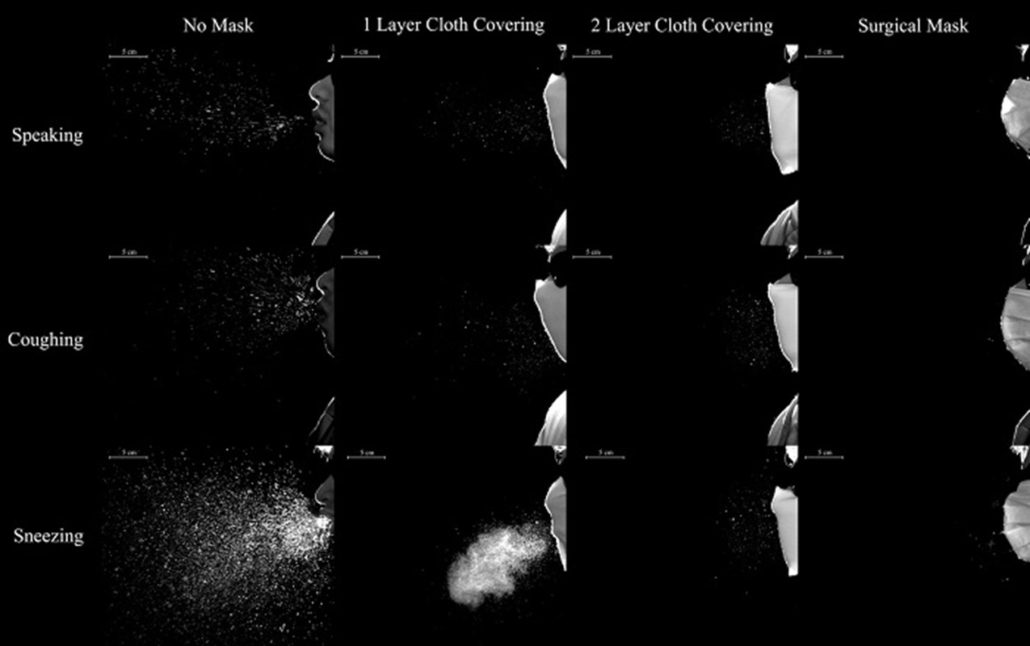

Meta-analysis is hard science, so setting yourself up for success from the outset is crucial. However, the review’s methodology and its assumptions about transmission don’t achieve that. A systematic review is only as good as the rigour it employs. This review compared ‘apples with oranges’, combining health and community settings, and as the authors highlighted, there was ‘relatively low adherence with the interventions during the studies’. In this instance that means people didn’t actually wear a mask. That doesn’t mean they don’t work: There is a world of difference between the careful application of single-use masks around vulnerable people in care homes and the oft-observed ’mask-under the chin’ approach of waiting staff in trendy restaurants. This Review didn’t differentiate between them. As the image[i] below demonstrates it’s clear that masks reduce spread when worn properly.

The Review combined RCTs where masks were either worn ‘part of the time’ or ‘continuously’. However, as we know both COVID and influenza viruses are airborne and an unmasked person could be infected anywhere once they had removed the mask.

The efficacy of mask wearing was reviewed across a wide range of human and physical settings that bear little or no relation to each other. As the authors themselves state, “many of the trials were small and hence underpowered, and at high or unclear risk of bias due to poor reporting of methods and lack of blinding. The populations, outcomes, comparators, and interventions tested were heterogeneous.” As a result, the conclusions are woefully muddied.

If the goal is to reduce morbidity in the elderly or reduce hospitalization, rigorously designed studies must be conducted that properly examine the ability of specific well-defined measures to interrupt the chain of infection. Solving compliance is no simple matter, but accurate assessment of compliance with a given behaviour must be done as part of these studies, or its impact will be hugely underestimated.

To explain why the 78 studies included in the Cochrane Report confuse matters, Abaluk observes, ‘The underpowered studies often have extremely low compliance. You might say, “Ah, doesn’t this mean masks don’t work in practice because no one complies?” No, because sometimes there is high compliance – but it’s not achieved through the methods [applied] in the underpowered RCTs.’

The overall conclusions are heavily confounded by the choices made by the authors. First, many pre-COVID studies relied on the self-reporting of mask-wearing. Self-reporting is notoriously unreliable. For example, one masking study in Kenya evidenced that self-reported use was 76% vs. actual use of 5% (REF). How do we draw conclusions about mask-wearing when the likely behavioural differences between the treatment and control groups are not significant? Secondly, studies need specificity. The circumstances required for an individual to spread a respiratory disease are specific to the disease and the current viral load shedding from the infected person. Trying to compare studies of influenza, inherited from prior iterations of the study, to the COVID studies obscures the important conclusion from the more recent trials. The COVID era studies, randomized controlled trials under conditions of high disease burden, show significant reductions in transmission attributable to widespread mask usage.

There is, undoubtedly, a huge amount we don’t know in this area, but the Review and its attendant press coverage are giving a very misleading impression of where the uncertainty lies. And it also takes a giant step backwards in terms of the knowledge we have gained in recent years. We should expect more from our investments in science. The public and our policy makers need evidence to guide our behaviours in response to our own practice of hygiene. To suggest ‘masks mandates did nothing’ is not only wrong, it would, in the face of another pandemic, be damaging.

The bottom line is that well-performed, randomized controlled trials show masks work. The complete flattening of the 2021 flu season demonstrates this . https://www.nbcnews.com/health/health-news/after-year-virtually-no-flu-scientists-worry-next-season-could-n1266534)

We should be asking science to fill the gaps in our knowledge and understanding and then use that high quality science to drive policy. The potpourri approach of the Cochrane Review that tried to review a set of miscellaneous studies fails to achieve that.

It is this wholesale failure that sits at the heart of the Cochrane Review. A small number of rigorous studies have shown us that when done well, scientific methods can show us what works. Policymakers need that good science to make informed decisions about public health interventions. It is unfortunate that this Review doesn’t recognise that.